The following article was a WHHS Heritage Banquet address by Rev. David Curry in 2003. It has been converted from a pdf file to be shared here.

Alden Nowlan: The Forgotten Poet of Stanley

I would like to thank the West Hants Historical Society for the privilege of speaking this evening and to commend the Society for recognising the very important part that literature plays in our heritage.

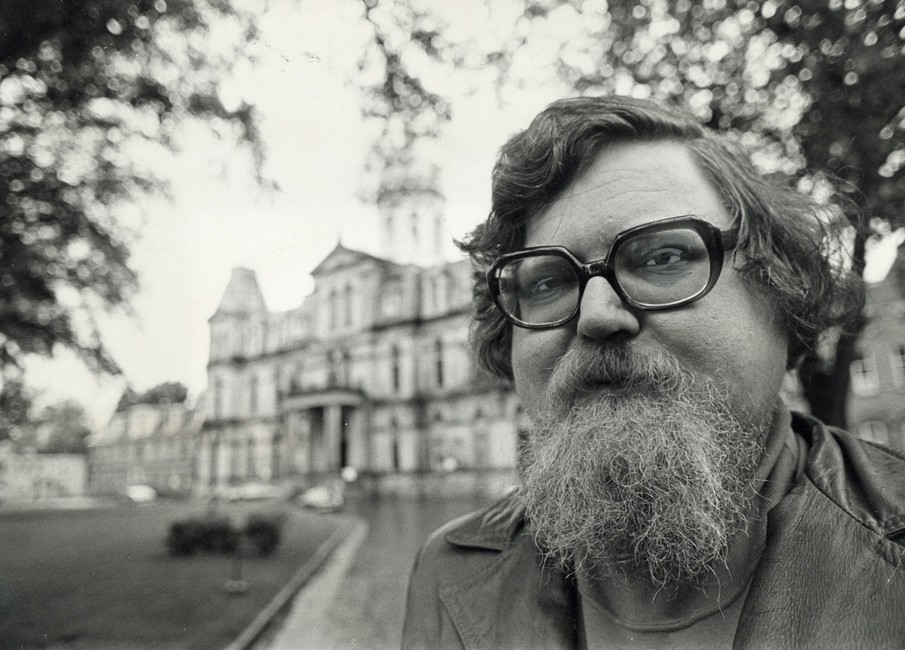

I have been asked to speak about Alden Nowlan, one of Canada’s great but almost forgotten poets and writers. Born on January 25, 1933, he was largely selfeducated, having left school in the midst of grade five to work at a variety of labouring jobs – pulp cutter, farmhand, sawmill worker, night watchman, ditchdigger and logger – before landing himself a job in journalism at the age of 19 in Hartland, New Brunswick by type-writing his own reference letter. His work with the local weekly, The Observer, first as a reporter then as news editor, was supplemented by a miscellany of other jobs, even that of a manager of a country and western band, George Shaw and the Green Valley Ranch Boys. At the same time he became involved in provincial politics, campaigning for Richard Hatfield and the Tories. Like many Maritimers, he could speak of the Nation’s Capital, Ottawa, with a certain degree of skepticism as being a city utterly divorced from reality. During his eleven years in Hartland, he also published six books of poetry, having come to the attention of Fred Cogswell and Desmond Pacey at the University of New Brunswick in Fredericton.

In 1963, he left Hartland to join The Telegraph-Journal in Saint John, New Brunswick. He was awarded the prestigious Guggenheim Fellowship in 1967, the same year that he won the Governor General’s Award for Poetry for a collection of poems entitled Bread, Wine and Salt. He was made Writer-in-Residence at the University of New Brunswick in 1968 and also received a Canada Council Special Award.

Alden Nowlan became something of a one man literary institution while at the University of New Brunswick. Along with other awards – the President’s Medal of the University of Western Ontario for short fiction in 1970 and 1972, the Canadian Author’s Association Silver Medal for Poetry in 1977, the Queen’s Silver Jubilee Medal in 1978, the Evelyn Richardson Award for non-fiction in 1979 – he was granted an Honorary Doctorate from UNB in 1971 and one from Dalhousie in 1976. A fruitful collaboration with Walter Learning at Theatre New Brunswick resulted in a number of dramas some of which were adapted for radio and some for television.

He died on June 27, 1983 in Fredericton; a prolific writer, poet, playwright, journalist, a major voice in Canadian letters, survived by his wife Claudine (Orser) and his step-son John. He was buried, appropriately enough, in what

might be called a kind of poet’s corner, near the graves of such literary figures as Charles G.D. Roberts and Bliss Carman. As Alden Nowlan’s most recent biographer, Patrick Toner, describes it, A large Celtic cross mark[s] the grave of an Irishman from Nova Scotia.

An Irishman from Nova Scotia. Indeed. The poems and writings of Alden Nowlan are standard features in a number of anthologies of Canadian and Maritime literature. In those anthologies, he is variously said to be born in Windsor or near Windsor, Nova Scotia. About his actual birthplace, there is a strange silence, almost as if there was a slight hesitation, even a sense of unease about naming the place of his birth. His biography tells us, of course, as does Robert Gibbs’ estimable biocritical essay Various Persons Named Alden Nowlan. His birthplace, as I am sure all of you know, is not Windsor but Stanley.

Alden Nowlan is the forgotten poet of Stanley, Nova Scotia.

Stanley was not only the place of his birth but, in some sense, the fons et origo of his poetic imagination, the place which played no small role in shaping his understanding of what belongs to our Canadian identity and to his articulation of the things which are. Some of those things are painful and fearful to behold, both for him and for Stanley. Stanley was for him Desolation Creek and the slough of despond, images conjured from John Bunyan’s Pilgrim’s Progress, though we also might remind ourselves that there are those who going through the Vale of Misery use it for a well(Psalm 84.6). Yet as the quote from the Revelation of St. John the Divine which adorns the collection of poems entitled The Things Which Are suggests, there is a kind of necessity, perhaps even a divine necessity, to the writing and to the reading. Write the things which thou hast seen and the things which are. It belongs to the vocation of the poet. A poet is a maker, a maker with words, but only out of what he sees.

Poets, like prophets and preachers, as it is proverbially said, have no honour in their own country. There is no monument, no memorial, no acknowledgment in Stanley to their greatest son.Since giving this paper on February 8th, 2003, a monument honouring Alden Nowlan has been erected in Stanley, Nova Scotia in 2004. There is, however, a plaque in the Windsor Library, a testament to Nowlan’s frequent use of the books there in the process of his selfeducation and to the kindness and encouragement of the Librarian, Eleanor Geary. But in some sense, Alden Nowlan’s work is a monument to Stanley, to the power of the land which shapes the landscape of the soul. In his writing, imaginative and disturbing, Stanley becomes, for good and for ill, a kind of Canadian Everywhere, reminding us of the rural realities of Canadian life, realities which we forget at our peril. What Alden Nowlan reminds us, in part through the fictional remaking of the facts of his past, are the things which belong to the relentless struggle for survival.

… I, walking backwards in obedience

to the wind, am possessed

of the fearful knowledge

my compatriots share

but almost never utter:

this is a country

where a man can die

simply from being

caught outside.

as he suggests in his poem Canadian January Night (1971).

About the more immediate landscape of East Hants County, he observes that,

Ours was a windy country, and its crops

were never frivolous, malicious rocks

kicked at the plow and skinny cattle broke

ditch ice for mud to drink and pigs were axed.

An early poem entitled A Poem To My Mother, later changed to The White Goddess, it signals the harsh realities of life and death in the thin-soil land of rural poverty in East Hants, the fears and sensitivities of a boy of twelve finding the young bull drowned, his shoulders wedged/into a sunken hogshead in the pasture, and the remembrance or the longing for the gentle caresses of a mother’s love, the kiss/your fingers sang into my hair all night, against the violent wildness of an unforgiving land without and within our souls – themes which recur in various and ambiguous ways throughout his literary career.

His poems especially face the fears of abandonment and neglect, of loneliness and the bitter sense of the pointlessness of life against which the writer at once discovers and creates a world. Writing was Alden Nowlan’s form of the struggle to survive. Above all else, it seems to me, that struggle meant naming and confronting the pathetic fatalism of the genes, we might say, the fatalism of family, the fatalism of the bog Irish of the Newport-Douglas settlements and by extension the forms of fatalism belonging to post-modernism.

I was an alien

in the village where

I was born,

three thousand miles away,

am as much

and no more

an alien here.

….

So nobody tries to change me

or even dreams it possible

for me to behave

in any other way.

Few poets have explored or understood the frustrations and the sense of futility born out of the spirit of fatalism or have written about it so eloquently, so clearly and so directly as Alden Nowlan. Ultimately, his work signals the possibilities of freedom, hope and life and, above all, demonstrates a passionate understanding of those who struggle against hardship and poverty, an understanding which is neither blind nor sentimental about the violence and the abuse, the folly and the rage of those who know and do not know or who do not know that they know what they confront as unmovable, inescapable forces. The poets help us to see but only out of what they have seen.

Every picture was a vision

sent by God; my mother’s Kodak, with its black snout,

was a thing of mystery: once I unwound a film,

in search of the pictures inside it, and found nothing.

It was not merely the pictures; every morning

we sang God save the King, and another hymn,

such as Jesus loves me. Nobody ever said

we belonged to God and the King; there was no need to say

it;

they were there, as our grandparents were there: nobody

had to say,

this is your grandmother, this is your grandfather; we had

always known it.

To put in another way, we no more believed in Kings

than we believed in Uncles; there was a blood relationship

involved, and like any other blood relationship,

it was nothing to make a fuss about, yet something

that nothing could alter….

(from The Country I was Born in was Ruled by Kings)

But to arrive at this point where a blood relationship [is] nothing to make a fuss about, having recognised that it is something that nothing could alter, was no small feat. It meant confronting the pain and the hurt in his own life about difficult and troubling family relationships and about a community which doubtless found the form of his struggle to survive simply incomprehensible.

The first poem in his first collection of poetry, The Rose and the Puritan (1958), captures his sense of this incomprehension of the community and the sense of censure towards the literary and creative act.

The neighbours, in a Sunday meeting mood,

Would roll sweet bits of pity on their tongues

And wonder gravely how the honest Browns

Could breed so little virtue in their sons.

For Jimmie whimpered when he saw a crow

Come down in answer to a classmate’s rock,

And fondled roses like a foolish girl,

And quoted school-book poets when he talked.

And Tom shaped women with his pocket knife

From bits of wood, beneath a lazy tree,

Or frightened village maids with silly tales

About the beauty of love’s ecstasy.

And John, the eldest, once as mad as they,

But now subdued with children, farm and wife,

Threw all his earnings into books and rum –

And cursed the bitter pointlessness of life.

The community – these neighbours in [their] Sunday meeting mood – is at once Stanley and more than Stanley. It is every community in its unawareness of the power and the necessity of words and art, every community where religion has been falsified and calcified into moral and political correctness and is dead to the living word. Alden Nowlan challenges us in those communities wherever we are.

It is much harder to confront and to come to terms with the pain and the hurt belonging to the fatalism of the family. And perhaps no poem better captures the poignancy of that pain and overcomes it than the last poem in the collection known as Smoked Glass (1977). The poem is entitled, significantly it seems to me, It’s good to be here, echoing the words of Peter upon beholding Christ transfigured on the mountain-top; It is good to be here, he had said.

I’m in trouble, she said

to him. That was the first

time in history that anyone

had ever spoken of me.

It was 1932 when she

was just fourteen years old

and men like him

worked all day for

one stinking dollar.

There’s quinine, she said.

That’s bullshit, he told her.

Then she cried and then

for a long time neither of them

said anything at all and then

their voices kept rising until

they were screaming at each other

and then there was another long silence and then

they began to talk very quietly and at last he said,

well, I guess we’ll just have to make the best of it.

While I lay curled up,

my heart beating,

in the darkness inside her.

Fiction, Timothy Findley observes, is about achieving the clarity obscured by facts. The facts are these: Freeman Nowlan was 28 years old and Grace Reese was 14 years old when Alden Nowlan was born in Stanley, Nova Scotia on January 25, 1933. Their marriage didn’t work. Allegedly, the age differential, Grace’s stepping out on him to dances with other men, and Freeman’s drinking all contributed to their separation shortly after the birth of Alden’s biological sister, Harriet, who was born in 1935. From about 1937 to 1940, Alden and Harriet were raised by Grace’s mother Leonora or Nora (Sanford) Reese in Mosherville until Nora’s death in 1940. Then, they moved back to Freeman’s house in Stanley where he had persuaded his mother Emma to look after the children.

The fiction has to do with the attempt to bring clarity to the sense of abandonment and dislocation and to understand the forces at work in the world around him and within him. As he suggests in his novel Various Persons Named Kevin O’Brien, we return to the past and change it, change it not so much by the reconstruction of facts and events as through the effort to understand the motivations and intentions of ourselves and others. There may be the colourings of romanticism but there may also be breakthroughs of the understanding.

So much of Canadian literature is shaped by the land and by the strongly felt necessity to articulate and communicate an understanding of one’s place and one’s identity. Ernest Buckler’s wonderful novel The Mountain and the Valley is framed by the image of a hooked rug in which all the tangled threads of human lives are woven into a kind of pattern. Just so, Alden Nowlan’s writing is about weaving his story, a story which, in turn, shapes other stories.

David Adams Richards, one of Canada’s outstanding authors, identifies Alden Nowlan as one of the great influences on his writing, naming him along with Faulkner, Ernest Buckler and Dostoevsky. Not bad company for a boy from

Stanley! Richards’ powerful and poignant novel, Mercy among the Children, echoes many of the same themes as Alden Nowlan’s writings. I like to think that, perhaps, in the figures of Sydney Henderson, a gentle, sensitive and selfeducated man who lives by the words of what he so carefully and thoughtfully reads, and his son Lyle who struggles to redeem the story of his father from the world of violence and incomprehension, lives something of the character of Alden Nowlan.

Without trying to chronicle or second-guess the hardships of his youth, it is not too much to say that the community of Stanley found Alden Nowlan more than a little strange. Though leaving school after grade four and only part way through grade five, he continued to read and read and read, whether it was books from the Windsor Library or publications which he got for free from the classifieds of the Family Herald – a truly bizarre collection of materials on a great number of religions and philosophies as well as on political philosophy, including communist literature. He came to identify himself as a Communist. He build a structure in a swamp near the house which he called the Nylonian Church Upon the Rock where at night by lamplight he could be heard ranting and raving about damnation and salvation.

Actually, it seems that what he was doing was reading out loud from the various publications which he had received. But as Patrick Toner suggests, ranting and reading about demons were both considered by local people to be the acts of a madman. Physically ill in 1946 he became quite despondent in 1947 after the death of his paternal grandmother and was sent to the Nova Scotia hospital in Dartmouth, returning in 1948. In 1949, he got a job at Russell Palmer’s Sawmill which he lost early in 1951 when it came out that he had been writing articles for

communist newspapers.

Now the point of mentioning these facts is that they become the material of his fiction in which there develops a kind of redemption of the past. The poem Weakness gives us a glimpse of the violent desperation of his father but also conveys a sense of despairing gentleness in the face of the things that can’t be changed. Nowlan came to recognise that being afraid of weakness, as he puts it in the poem Cousins, is part of the fatalism, but in a moment of gentleness we see the unnecessary gesture which belongs to a freedom beyond the fatalism.

Old mare whose eyes

are like cracked marbles

drools blood in her mash,

shivers in her jute blanket.

My father hates weakness worse than hail;

in the morning

without haste

he will shoot her in the ear, once,

shovel her under in the north pasture.

Tonight

leaving the stables,

he stands his lantern on an over-turned water pail,

turns,

cursing her for a bad bargain,

and spreads his coat

carefully over her sick shoulders.

His reading of eclectic religious and political literature in his tower in a swamp will be reworked into the gentle, ironic and humorous short story, The Girl Who Went to Mexico which involves the same sense of the seemingly accidental yet providential chain of events which Ken Miller of the Windsor Tribune may well have set in motion in referring this young writer to another editor – the editor of the Hartland Observer, and which he writes about in the poem, What happened When He Went to the Store for Bread. In the short story, Sam Baxter, too, is accused behind his back of being a communist because of the literature which he receives for free in responding to ads in the magazine. The seemingly accidental series of events ultimately leads him to marriage and happiness all because of the girl who persuaded him to take out a magazine subscription to The Canadian Yeoman. Even the matter of being a communist is reworked in the novel Wanton Trooper where the fictional Uncle Kaye calls it equalizin’.

The point is that in facing the forms of fatalism in the communities of his past and present the poet and writer has discovered freedom and perhaps even grace, but certainly love. Great things have happened.

We were talking about the great things

that have happened in our lifetimes;

and I said, oh, I suppose the moon landing

was the greatest thing that has happened

in my time. But, of course, we were all lying.

The truth is the moon landing didn’t mean

one-tenth as much to me as one night in 1963

when we lived in a three-room flat in what once had been

the mansion of some Victorian merchant prince

(our kitchen had been a clothes closet, I’m sure),

on a street where by now nobody lived

who could afford to live anywhere else.

That night, the three of us, Claudine, Johnnie and me,

woke up at half-past four in the morning

and ate cinnamon toast together.

Is that all? I hear somebody ask.

Oh, but we were silly with sleepiness

and, under our windows, the street-cleaners

were working their machines and conversing in Italian, and

everything was strange without being threatening,

even the tea-kettle whistled differently

than in the daytime: it was like the feeling

you get sometimes in a country you’ve never visited

before, when the bread doesn’t taste quite the same,

the butter is a small adventure, and they put

paprika on the table instead of pepper,

except that there was nobody in this country

except the three of us, half-tipsy with the wonder

of being alive, and wholly enveloped in love.

(from Great Things have Happened)

Alden Nowlan is often called the People’s Poet. This seems to me somewhat misleading if not dangerously condescending. Even though I think that with his rich baritone voice, at least before his surgeries in 1966 for cancer of the thyroid, he could probably sing better than Leonard Cohen, (though, perhaps, that isn’t saying much!), certainly better than Bob Dylan, (that, too, isn’t saying very much!), and likely reach a few more notes than Ann Murray (nor is that saying a whole lot!), his poems do not lend themselves to popular music or to popular

culture in general. This is not to say that they are academic and erudite in some self-conscious manner. By no means. They are challenging and thoughtful. They have a primitive vitality and vigour about them which is disturbing and yet compelling.

Robert Bly of Iron John fame, for instance, celebrates Alden Nowlan as one of those poets who belong to the umbrella rippers, one who faces his fears and ours, one who is not afraid of the raw edges of life, one who exposes the pretensions and the hypocrisies of our pseudo-sophistications. I think that is true but it doesn’t stop there. In facing those fears honestly and clearly without cant or self-pity, he allows for the possibilities of new things, of greater things, to appear. He helps us to understand, to see what he has come to see about ourselves, the world from which we come and the world which we confront.

Perhaps, this is his greatness.

I would be the greatest poet the world has ever known

if only I could make you see

here on the page

sunlight

a sparrow

three kernels of popcorn

spilled on the snow. – (Greatness)

And perhaps he has.

(Rev’d) David Curry

February 8, 2003

West Hants Heritage Banquet

Brooklyn, NS

About the author:

A native of Falmouth, Nova Scotia, David and his wife Marilyn have three children Elizabeth, Joel, and Madeleine.

A graduate of the University of King’s College (B.A. Hon.), Dalhousie University (M.A.), Harvard University, Cambridge, Massachusetts (M.T.S.), and Trinity College, University of Toronto (M.Div.), and ordained to the priesthood in 1982, David was New Testament Greek Tutor at Trinity College (1980-1982), Dean and Lecturer in Humanities and Social Sciences at the University of King’s College (1982-1985), Curate at The Church of The Advent in Boston, Massachusetts (1985-1990), and Rector-Designate of The Combined Parishes of Liscombe and Port Bickerton of the Diocese of Nova Scotia and Prince Edward Island on Nova Scotia’s Eastern Shore (1990-1998).

He is currently the Rector of the Anglican Parish of Christ Church, Windsor, Chaplain and Senior School English and Philosophy teacher in the International Baccalaureate programme at King’s-Edgehill School. He has spoken and written on matters of theology, liturgy, history and literature. He is also Vice-President of the Prayer Book Society of Canada and the Local Vicar of the Ste. Croix Branch of an Anglican Priests’ Society, the Society of the Holy Cross (Societas Sanctae Crucis, SSC).