This address was given by Reverend David Curry on November 1st, 2007 to the West Hants Historical Society in Windsor, NS.

“Thy Sweet Love Remember’d”: A Poet & A Church

“When in disgrace with fortune and men’s eyes,” Shakespeare’s Sonnet # 29 begins, William Shakespeare, The Sonnets of Shakespeare (New York, Paddington Press, Royal Shakespeare Theatre Edition, 1974) Sonnet # 29. entering into a meditative discourse on the vagaries of human ambition and the vanities of fame and renown, “troubling deaf heaven with my bootless cries,” and even reaching the brink of dark despair, “yet in these thoughts myself almost despising,” when suddenly the whole poem shifts in a line, “haply I think on thee, and then,” then all is changed and the sonnet concludes “for thy sweet love remember’d such wealth brings/that then I scorn to change my state with kings.” Thy sweet love remember’d, the divine love, perhaps? that underlies and shapes and informs all our loves and all our lives.

It serves, perhaps, as a fitting metaphor for the task of our age. In the culture of scattered minds and, appropriately, in the season of scattered leaves, there is a kind of necessity for the deep and careful remembering of what belongs to identity and place. We live, as the Canadian philosopher, Charles Taylor suggests, in the “disenchanted world” of “A Secular Age” and culture,Charles Taylor, A Secular Age, ( Cambridge, MA, Belknap Press of Harvard Univ. Press, 2007). a world disenchanted and disengaged from the spiritual principles that gave it birth and vitality, a world which, paradoxically, we cannot even begin to understand without rethinking the place and role of religion in shaping that world.

The paradox comes closer to home when you consider such things as the antics and bacchic revels of Halloween, an evocation of the superstitious world of pagan spirits, on the one hand, and a crass and cynical play to our relentless consumer appetites, on the other hand. I don’t quite know what we are teaching our kids. How to be terrorists or how to be beggars! Trick or treat, indeed! It is a far remove from the real meaning of Halloween, namely, the Eve of All Hallows, the commemorative celebration of all the saints, the holy ones,’ confessed in the Creed as the Communion of Saints. It sets before us a glorious vision of the human community redeemed.

Remembering is not simply about a “Nostalgia for the Absolute,” to use George Steiner’s title of his 1974 Massey Lectures which critiqued the false gods of Marxist Socialism, Freudian Psychology and Levi-Straussian Anthropology which had rushed in to fill the void of the banished God of the western and Christian world.George Steiner, Nostalgia for the Absolute (Toronto, ON, Anansi Press, CBC Massey Lecture Series, 1974). No. But, perhaps, through the barren emptiness of the disenchanted world of the disintegrated self, where the cult of personality has displaced the culture of character, we might begin to discover the need to remember the principles and ideals that convey dignity and purpose to our lives in the communities where we are placed.

Alberto Manguel, in the first of this year’s Massey Lecture Series, The City of Words, speaks of the literary voice in the contemporary world as the voice of Cassandra, using the German writer Alfred Doblin as an example.Alberto Manguel, The City of Words (Anasi Press, Toronto, ON, CBC Massey Lecture Series, 2007). Doblin, who managed to flee Nazi Germany to America, but whose books were burnt in 1933 along with Erich Marie Remarque’s classic, All Quiet on the Western Front, returned to Germany after the war to address a country whose language and culture had been shattered. For him the task was that of a rigorous and unsentimental kind of remembering that would allow for the finding of “a collective identity that compounded personal freedom with a pitiless objectivity’.”Alberto Manguel, The City of Words, p. 20.

Addressing an audience in Berlin in 1945, he argued that “you have to sit in the ruins for a long time and let them affect you, and feel the pain and the judgment.”Alberto Manguel, The City of Words, p. 20. In response to journalistic disdain and dismissal under the guise of claiming to have heard that before, he replied “you haven’t really heard it. And if you heard it with your ears” “ a biblical echo to “ears have they but hear not” “you didn’t comprehend it, and you’ll never comprehend it because you don’t want to.”Alberto Manguel, The City of Words, p. 20. Strong words about the necessity of remembering in the face of a willful forgetting. It may even be harder for the victors of the great conflicts to think clearly about the spoils of war in what we might call, the ruins of victory.

But “in the greyness of the year, comes Christ the King,” with apologies to T.S. Eliot,T. S. Eliot, The Complete Poems and Playsm 1909-1950 (New York, Harcourt, Brace & World, Inc.,1971) Poems 1920, Gerontion,’ p. 21. and we are awakened to another view of our humanity. Such are the possibilities of our November remembering, both sacred and secular.

It is a remembering that happens through listening to the voices of the poets, past and present, to be sure. But it is also a remembering that happens by attending to the things that stand in our midst, like the churches of our towns and villages, churches that stand as sentinels to the presence of God in human lives even in the culture of our disenchantment.

The poets and the churches.

We do not, perhaps, think of them together, but that is part of the problem. Theology, after all, is very much a poetic affair through which the high things of God are glimpsed and seen, touched and communicated, grasped and realized as near and present in human lives and in ways that can be truly transformative.

Tonight, I would like to touch briefly upon some of the features of Christ Church in relation to the town of Windsor, particularly with respect to the 112th battalion, but by way of incorporating some of the poetry of Sophie Almon Hensley, another poet whose writings are among the scattered leaves of literature that have a close connection to Windsor and the valley. In a way, what I have to say is precisely about the connections; the connection between Church and community, between Christ Church and the Schools and the Military, for instance, here in Windsor. The recently celebrated 125th anniversary of the present building of Christ Church provides the occasion for such

reflections.

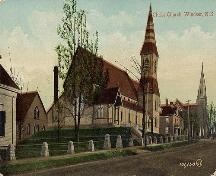

On October 14th, 1882, the cornerstone for the present Christ Church was laid. Built by Joseph Taylor, a noted builder in Windsor, the structure was designed by a Worcester Massachusetts architect, Mr. Stephen Earle, noted for his versatile handling of a variety of architectural styles including the neo-gothic. His plans for Trinity Church, Digby, were provided for Christ Church free of charge on the condition that they not be altered. The building of Christ Church took almost two years to complete and the work excited considerable interest in Windsor which regarded the edifice arising in their midst with a kind of pride that was by no means limited to just Anglicans. The building was seen as an ornament to the town. Completed in March of 1884, the first service was held on Sunday, March 2nd, 1884. An extensive article in the Hants Journal on March 5th illustrates the significance of the building for the town.David Curry, Gates of Heaven: Sweet Love Remembered (Christ Church, Windsor, 125th Anniversary Commemoration) pp. 16-21.

There is a marvellous quality of understatement and social commentary in the editorial remark, for instance, that “a people only moderate in numbers and not fabulous for wealth” had accomplished the building of structure regarded as “one of the finest churches” in Windsor.David Curry, Gates, p. 19. Henry Youle Hind writing about the Parish Burying Ground in 1889 commented that at that time there were only one hundred and thirty Anglican families within a two mile radius of the Parish.Henry Youle Hind, An Early History of Windsor, Nova Scotia (Windsor, Jas. J. Anslow, at the Hants Journal Office, 1889, reprinted by Lancelot Press, Hantsport, NS, 1989)p. 93. It was the ladies of the Church, of course, who labored most industriously and indefatigably to raise the funds and who played a major role as well in the ensuing decades with respect to its furnishings and enhancements.

The occasion for the building of the present Christ Church was a fire in 1881 that seriously damaged the Chapel-of-Ease, St. Matthew’s, formerly located on Grey Street between Stannus and Albert. Nothing remains of that structure other than an unattributed sketch. It was, however, not highly regarded as much of an edifice. Bishop Hibbert Binney, the fourth bishop of the diocese, actually claimed that “it wouldn’t make a respectable barn!”

L.S. Loomer, Windsor;Nova Scotia: A Journey in History (Windsor, NS, West Hants Historical Society, 1996) p. 240.

The original Christ Church was a structure largely designed by the first Bishop of Nova Scotia, Charles Inglis, indeed, the first bishop consecrated for a diocese outside the British Isles, who played a major role in shaping the life of Windsor and Nova Scotia, another one of the firsts in a town of many firsts but one which, I fear, is often overlooked. The building of the first Christ Church had implications for more than Windsor; it was intended, as Brian Cuthbertson notes, “to be the finest new church in the diocese.”Brian Cuthbertson, The First Bishop (Halifax,NS, Waegwoltic Press, 1987) p. 124. There was actually talk, too, about making Windsor the Episcopal See for the diocese which initially stretched from the shores of the Atlantic to what is now Detroit. Somehow Halifax won out. The original Christ Church, built on what is now called the Old Parish Burying Grounds, served as well as the Chapel for the School and University founded at the initiative of Inglis in 1788 and 1789 respectively. It stood until it was destroyed by arson on July 1st, 1892.

In an age before the automobile, the first Christ Church was just far enough away to be inconvenient for the townspeople of Windsor. Thus, in 1845, a Chapel-of-Ease, called St. Matthew’s, was built on land purchased for that purpose by Judge Haliburton and with the approval and encouragement of the third Bishop of Nova Scotia, Charles Inglis’ son, John. His son, Charles’ grandson, was General Sir John Eardley Wilmot Inglis, a student at King’s and a famous military figure who distinguished himself in the Indian Mutiny in the mid-19th century as “the hero of Lucknow,” taking command of the besieged residency after the death of Sir Henry Lawrence. Inglis was made a major-general and knighted for his part in the defense of Lucknow.

The Hants Journal editorial of March 5th, 1884 bears more than eloquent testimony to the significance of the building of Christ Church for the town, commenting extensively on all aspects of the building and noting in particular how the timber used in the frame and elsewhere in the building was all local wood, a testament to the stands of trees that were once part and parcel of the area. Equally outstanding, was the role that Christ Church played only thirteen years after its erection. It was not only the one church within the town proper that survived the Great Fire of 1897, but between the two Schools and the University and the Parish, Anglican institutions provided sanctuary for the other denominations in the town until new structures could be built.

Christ Church survived the fire, of course, because of the timely intervention of students from the school and college who poured water, and apparently, even milk on the roof to save the Church from being utterly consumed in the conflagration. They also, and wisely, saved the tavern across the street! Windsor rebounded rather quickly from the fire but it was another fire that had much more devastating effects upon Christ Church and Windsor, and that was the fire at King’s in 1920 that resulted in the University re-locating to Halifax and entering into an association with Dalhousie University.

But the building of Christ Church stands out as a monumental undertaking and one speaks to us about the past of Windsor in ways that we may not always be ready to appreciate. The simple point is that the town was more-or-less on the map, both in terms of literature and commerce. Charles G.D. Roberts, an outstanding figure in the area of English literature and letters taught at King’s College from 1885 to 1895. He would have been in the newly built Christ Church. He spoke of the “almost urban flavor” of Windsor in the 1880s and 90s, a town of intellectual and commercial interests, noting that it was the third largest shipping port in Canada at that time after St. John, New

Brunswick, and Montreal.Loomer, Windsor, p. 235

But what about the poet?

Sophie Almon Hensley

Sophie Margaretta, née Almon, Hensley was born in Bridgetown, Nova Scotia on May 31st, 1866 and became a protégé of Charles G. D. Roberts here in Windsor before finding her own voice and thought as “an elegant woman and an independent thinker,” as Gwendolyn Davies has described her.

Gwendolyn Davies, Dictionary of Literary Biography, (99. 165) in Wanda Campbell, Sophie Almon Hensley, http://www.uwo.ca/english/canadianpoetry/hidden_rooms/sophia_almon_hensley.htm, accessed March 28th, 2006.

Married to Hubert Hensley, a Halifax lawyer, she lived in New York, in France, and even on the Island of Jersey. She died in Windsor on February 10th, 1946. Much of her earlier poetry shows the influence of Charles G.D. Roberts with its romanticism of nature and with a similar use of words and images. But a certain moral quality obtrudes more directly in her poems than in his. Like him, there is a strong sense of the land as the place of one’s identity as her 1934 poem, Repatriated, suggests, a poem that evokes the pull of the lands of the Avon though one has traveled and lived far from its valleys and shores.

Repatriated

All my dear childhood and the budding years,

Glamorous and glowing, knew the spruce-bound hills,

The ruddy Avon, and the towering tiers

Of bleak-browed Blomidon; the wood-locked mills;

The apple-orchards dropping yellow fruit,

The fields of grass and grain of Acadie.

Through long maturer years, with magic mute

In clamour of great cities, I could see,

Eyes closed, the marshes that I loved, the stream

Of plover, hear the raucous call of crows,

And knew a deep nostalgia through my dream.

Out where the strange Pacific ebbs and flows,

Through the wild roads and hills of Santa Fé,

Far on the Tucson desert, and along

The Apache Trail, a thousand wonders lay.

Grandeur I knew, and warmth, and friendliness

In the great Western States, and health and play;

But always was I alien, nationless,

With voices calling from St. Mary’s Bay,

From little sleepy towns of Gaspereaux.

I have come home from world-wracked troublous climes

To the calm haven of the Maritimes,

Calm without fixity, a land of men

Rugged and real, my people. All of me”

Sprung from their soil, their forests, and their sea,

Canadian in blood and hope and heart”

Calls to my people. And so, in the gloam,

My eventide, ready to do my part,

I have come home.

Somehow the sweet love remembered’ of the landscape of the Maritimes retains a hold on her mind and soul.

An early volume of her poetry was printed here in Windsor for the author by J.J. Anslow of the Hants Journal in April 1889 intended for private circulation. One of those poems speaks to a religious sensibility about truths held sacred and if not known at least hinted at through the medium of the natural world from which things are felt and seen and then are known. Entitled, There is no God, it interrogates the claim rhetorically by way of reference to what is all around us.Project Gutenborg EBook of Poems, by Sophie Almon Hensley, http://www.gutenberg.org/files/17936/17936-h/17936-h.htm, accessed March 28th, 2006. It has the charm of a certain directness of thought that provides a kind of counter to the dogmas of atheism.

There is no God

There is no God? If one should stand at noon

Where the glow rests, and the warm sunlight plays,

Where earth is gladdened by the cordial rays

And blossoms answering, where the calm lagoon

Gives back the brightness of the heart of June,

And he should say: “There is no sun””the day’s

Fair shew still round him,”should we lose the blaze

And warmth, and weep that day has gone so soon?

Nay, there would be one word, one only thought,

“The man is blind!” and throbs of pitying scorn

Would rouse the heart, and stir the wondering mind.

We feel, and see, and therefore know,”the morn

With blush of youth ne’er left us till it brought

Promise of full-grown day. “The man is blind!”

The 112th Battalion & Christ Church

But between the fires of 1898 and 1920, there was “the war to end all wars,” and no remembrance of the history of Christ Church or of Windsor itself can overlook the tremendous impact of war, especially the First World War, on the town and parish.What follows is taken more or less directly from David Curry, Gates of Heaven, pp. 71-78. Central to that consideration was the establishment of a battalion here in Windsor, a story in which the Parish of Christ Church played more than merely a minor role. It is the story of the 112th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force whose Colours continue to hang in Christ Church to this day.

The Venerable Archdeacon G.R. Martell, Rector of the Parish of Christ Church at that time, played a large role in the formation and recruitment of the 112th. Authority for recruiting was granted in November 1915 and by mid-April, 1916, the Battalion was at full strength with over 1200 men. Three months later, having been inspected by Major-General Sir Sam Hughes, the federal Minister of Militia, the battalion embarked to take its part in the great and defining contests of the twentieth century, but not as a battalion. Dissolved in 1917, its members served in the 25th Battalion and with the Royal Canadian Regiment as reinforcements, which achieved battle honours in the First World War at Arras, 1917 & 1918, Hill 70, Ypres, 1917, Amiens, Hindenburg Line, and the Pursuit to Mons.

Though the battalion included men born in such far-away places as Russia, Norway, Finland, Bermuda, South Africa, Syria, Gibraltar, England, Scotland, Ireland, the United States, Mexico, and Newfoundland, which was then a separate colony, the vast majority of the 112th Battalion was formed by men from rural Nova Scotia; over 130 alone from Hants County. The nominal roll contains many names belonging to Windsor and its immediate environs. Of the thirty-six officers, eleven came from the communities of Windsor, Falmouth and Hantsport: Lieutenant-Colonel H.B. Tremaine (Windsor), Major William Frederick D. Bremner (Castle Frederick), Captain Richard Thomson Christie (Windsor), Captain Randolph Winston Churchill (Hantsport), Captain William Wallace Judd (Windsor), Captain John St. Clair MacKay (Windsor), Lieutenant Walter Davenport Comstock (Hantsport), Lieutenant Raymond Watson Dill (Windsor), Lieutenant Ralph Shaw Parsons (Windsor), Lieutenant William John Sangster (Windsor), and Lieutenant Percy Lawrence Wilcox (Windsor).

The Colours were made by Mrs. Annie Pratt of Windsor and were presented to the Battalion on Friday evening July 21st at Victoria Park, the site of the present cenotaph commemorating the war dead of Hants County from the First and the Second World Wars and the Korean War. Mrs. H.B. Tremaine, the wife of commanding officer, Lieutenant-Colonel H.B. Tremaine, presented the Colours to the Battalion at a ceremony which featured addresses by the Chaplain, Captain G.R. Martell, Rector of Christchurch (sic), Mayor Roach of Windsor and others.

On Saturday, the 22nd of July, the Colours of the 112th Battalion of the Canadian Expeditionary Force were deposited in Christ Church at divine service attended by the officers and men of the 112th Battalion. The next day, Sunday, July 23rd, the battalion embarked at Halifax on H.M.T. Olympic, arriving at Liverpool, England on July 31st, ultimately being deployed in various Battalions already at the Front, including the famous 25th Battalion of the 2nd Division’s 5th Brigade and the Royal Canadian Regiment before being merged with the 26th Canadian Reserve Battalion in February, 1917.

Of the thirty-six officers of the 112th, eight would be killed in action during the last two years of the Great War, along with many of the men of the battalion who saw action in different theatres of the war at the Front. The Colours of the 112th, dedicated on the 22nd of July 1916 and later retired and encased in Christ Church, bear testimony to the connection between the Parish and the military community as well as to the tremendous sacrifices made by Maritime Canadians in the First World War.

Alongside the Colours in the Church, there is a picture of the Bugle Band of the 112th of which John Hughes, father-in-law of Mrs. Barbara Hughes, presently one of the Wardens of Christ Church, was a member. Another photo from the period shows John Hughes, Jim Vaughn, and Fred Mounce of Avondale in a lighter moment bearing what appears to be ‘the arms’ of a camp cleaning detail with John Hughes shouldering his broom in military fashion, as it were! All three would survive the war and return to contribute substantially to the community and the province.

A tablet “erected by the Congregation of Christ Church” commemorates “the valour of the Following Members of the Congregation Who Fell in the Great War” of 1914-1918: George Rigby Martell, Charles Henry Shaw, John Edward Taylor, Percy Franklin Seymour, Vernon William Spicer, William Cooke, Tom Dudley, John Reid and Maxwell Reid as well as “the placing in this Church of the Colours of the 112th Battalion C.E.F whose Officers and Men were faithful attendants at the services of the Church previous to their Departure for overseas in Defense of the Empire, July 1916”.

Of these nine names associated with Christ Church, Charles Henry Shaw and Vernon Wilson Spicer, and George Rigby Martell were members of the 112th Battalion. Martell was Captain and Chaplain of the 112th, but did not go overseas. He died, while still in military service, however, on June 17th, 1918. The rood or chancel screen was erected in his honour in 1920.

Further testimony to the role of Christ Church in the formation and life of the 112th is found in the sanctuary. The prie-dieu, or prayer desk, before the Bishop’s throne commemorates Clarence Cereno Currell Purdy of the 112th Battalion, C.E.F. “who died a Prisoner of War at Limbeck, Germany, October 1917, aged 21 years.” Made by his father, the kneeling desk was presented by his parents and family in May 1926 and serves as a salutary reminder of the role Christ Church played in the lives of the young men who went off to war and who paid the supreme sacrifice. Clarence Purdy, like Sophie Almon Hensley, was from Bridgetown, Annapolis County, Nova Scotia.

No poem captures more profoundly the intensity and the mixture of emotions stirred in the hearts of many who watched their sons preparing for war and, ultimately, for death while here in Windsor. Written in 1918, Sophie Almon Hensley’s poem serves as a fitting tribute to the 112th, to the connection between the 112th Battalion and the Parish of Christ Church and to the quality of remembering that is most especially our task and burden in this grey month of remembering.

Somewhere in France, 1918

Leave me alone here, proudly, with my dead,

Ye mothers of brave sons adventurous;

He who once prayed: “If it be possible

Let this cup pass” will arbitrate for us.

Your boy with iron nerves and careless smile

Marched gaily by and dreamed of glory’s goal;

Mine had blanched cheek, straight mouth and closegripped

hands

And prayed that somehow he might save his soul.

I do not grudge your ribbon or your cross,

The price of these my soldier, too, has paid;

I hug a prouder knowledge to my heart,

The mother of the boy who was afraid!

He was a tender child with nerves so keen

They doubled pain and magnified the sad;

He hated cruelty and things obscene

And in all high and holy things was glad.

And so he gave what others could not give,

The one supremest sacrifice he made,

A thing your brave boy could not understand;

He gave his all because he was afraid!

The poem is sometimes printed as ending there but it has a final stanza that adds to its poignancy and completes the scriptural and Christological connection to Christ’s prayer in the Garden of Gethsemane.Sophie Almon Hensley, “Courage” in Everybody’s Magazine (August 1939) and in The Way of a Woman and Other Poems (1928), but entitled “Somewhere in France 1918” in Canadian Poetry: From the Beginnings Through the First World War, ed. Carole Gerson and Gwendolyn Davies (Toronto, ON, McClelland & Stewart Inc., 1994) The former two citations are found in Wanda Campbell, Sophie Almon Hensley, http://www.uwo.ca/english/canadianpoetry/hidden_rooms/sophia_almon_hensley.htm, accessed March 28th, 2006.

Like a machine he fed the shining shell

Into a hungry maw from sun to sun;

And when at last the hour struck, and he fell

He smiled, and murmured: “Thank God, it is done.”

Ye glory well, ye mothers of brave sons

Eager and sinewy, in the part they played;

And England will remember, and repay,

And history will see their names arrayed

But God looked down upon my soldier-boy

Who set his teeth, and did his bit, and prayed

And understands why I am proud to be

The mother of the boy who was afraid!

It is about “thy sweet love remember’d,” perhaps, in the hardest and most poignant of situations, the loss of a child, in this case, a son killed in war. The poem places, as all true remembering does, our thoughts and memories with the eternal remembering of the God who knows us better than we know ourselves, the God who has entered into the sufferings of our world and day to bring us hope and salvation. Our Churches stand as sentinels in our communities to his continuing presence with us, the places of sweet love remember’d.

Address to the West Hants Historical Society

(Rev’d) David Curry

November 1st, 2007