The Great Windsor Fire of 1897: A Catastrophe and the Community's Rebirth

The most devastating event in the visual history of Windsor was the great fire of 1897. In it, the whole central portion of the largely wooden town was destroyed. Businesses were ruined, merchants left penniless, families left homeless and their only belongings, the clothes on their backs, some of the clothes merely nightgowns or shirts.

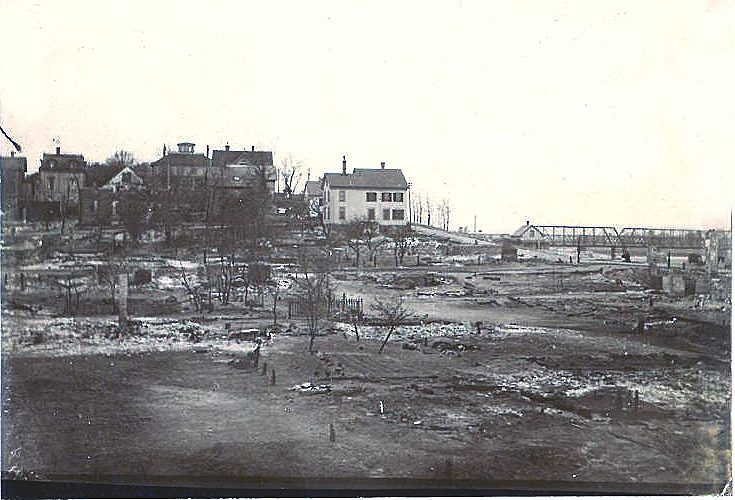

The fire occurred during a strong northwesterly gale of almost hurricane force. The smoke was visible seventy miles away. The smoldering ruins were not unlike pictures of European cities heavily bombed during the Second World War. Mercifully, there was no loss of life.

Who did it??

Assigning blame for the fire is long ago and far, far off. What caused it was carelessness. What allowed it to get out of hand divides between natural force and human incapability. The who’s and why’s are muddied in accusations and recriminations. Justice does not appear to have been well served. Nothing can be accomplished here by disinterring all of the contradicting fragments. The fire was one of those situations just waiting to happen.

For almost a century and a half the central portion of the town had been developing gradually of wood. Buildings became taller and distances between them narrower. Houses, barns, sheds and outbuildings were attached one to the next or so close they might as well have been. Old chimneys had been cracked by heat and not properly cleaned. Sheet metal stovepipes were becoming abundant. Flammable materials including kerosene and tarred rope were stored in many parts of the commercial area, particularly along the waterfront side of Water street.

There was no effective building code. There was no stringent fire regulation. There was a fire department that had a good deal of pride in its accomplishments. In the l880’s it had set a world record for its rapid handling of fire hose. The Hants Journal of 18 August 1886 carried a picture and a long account of this event, and the celebration dinner in Windsor that followed.

The fire department, dating from 1881, was very good with public displays. Its rate of success with serious fires was another matter. Much depends on early recognition and prompt response. Many times the fire fighters have not had a fair chance of success. In spite of that, sometimes the result has been little short of miraculous. Losses of property and life are usually recorded, and long remembered. There is infrequent mention of lives saved, and prevention of damage or destruction beyond the fire.

In the Hants Journal of 20 October, 1897, JJ Anslow’s anger surfaces again and again. He could not control it, and perhaps did not try. He had lost everything of his business except his faithful readers. “We little thought… that in a few brief hours the earnings of many years would be swept away in smoke and ashes…”

When did it start?

The fire occurred on Sunday morning 17 October 1897, beginning about 3 a.m. when the fire alarm was sounded.

The Hon. Monson Hoyt Goudge, who became president of the Legislative Council, was one of the Windsorians made homeless by the fire. His house, on King Street, was only a couple of doors up from Water street. He and his family took refuge in Victoria House in Halifax. He was one of the first people to respond to the fire alarm. He was then sixty-eight. He gave a good account of the events as they transpired.

” At three o’clock the alarm of fire was given and many people turned out… The town water service was called into use and a bucket brigade was organized, and by 4 o’clock the fire was practically at an end, it having been confined up to this time to the small and unimportant buildings in which it began. There had been no wind up to four o’clock. At this hour a breeze sprang into existence from the northwest, freshened to a gale and later developed into a hurricane, blowing fifty miles an hour. It attained its velocity with astonishing rapidity.

“Between the situation of the fire and the property immediately adjoining was an alley which acted like a funnel, up which the flames climbed in an instant. It was recognized that a large fire was a certainty. The flames had now a hold on a block of tall wooden buildings which would feed them like tinder. The streams of water from the plugs were as straws beating against a hurricane. We were powerless then in the presence of a calamity.

“Everything possible was done, but the fire spread in every direction, and burning brands were cast ahead of the conflagration and ignited other buildings. It was resolved after four o’clock to appeal to Halifax for assistance. Not being able to reach the centres necessary to communicate with the authorities of the Dominion Atlantic Railway, we took it upon ourselves to order a train sent from Halifax with assistance, signing the name of [superintendent] Gifkins to the communication. We had to do it.

“What happened from four o’clock to six o’clock passes description. People hurried out of their beds and houses and attempted to save their effects, goods, etc., but very little was accomplished. The stuff was burned on the street after being taken out, the owners having to leave it to save their lives.

“All the wharves and warehouses on the waterfront between Albert and King streets were burned. There was fortunately no shipping in to lose. At the corner of King and Water streets my store was left standing. This is the only place of business in the town not burned. Near-by two small dwellings were left standing. This was the extreme northern point of the burned district. The extreme south was Albert street.

“Every industrial establishment was burned, including the furniture factory and the Windsor iron works. The Pigeon fertilizer works and the cotton mills were outside the fire area and escaped. Every church except the Episcopalian was burned. How this escaped is a mystery.”

According to tradition, it was the students from King’s College, not angels, who kept pouring water on the roofs of the Christ Church buildings that saved them. They were also reputed to have saved the tavern across the street.

Initially, the estimated loss of property was two million dollars, little of which was insured, and that by no means to the limits. “… comparatively little insurance was carried.”

Firemen and others in Halifax, unable to get a special train, arrived on a regular morning run, bringing one steam fire engine, three horses and 800 feet of hose.

During the day, looting began. It was beyond control by the militia, firemen and the few police. The solution was to call in the Army, and the response was quick and effective. There were shots fired at robbers by the Army, but no one was injured. The undesirables had arrived on the first train from Halifax and broke into the Dufferin Hotel and stole silverware.

In Halifax, authorities lacked Mr. Goudge’s inventiveness in resorting to forgery to get the railway into action. General Montgomery Moore promptly sent out 150 of the Royal Berkshire Regiment with all sorts of supplies to go by train to Windsor. They were temporarily defeated by railway bureaucracy, probably making the general wish military law had been invoked.

The district militia commander sent a hundred blankets, and a hundred tents. Another three hundred tents, Imperial government property, were also sent along.

The fire, said the Journal, anonymously,”… wiped out half the township and four-fifths of the main part of the town. Hardly a single place of business remains and between 400 and 500 buildings are in ashes.

“The fire started … on Water street… and spread out from this point like a leaf or fan. It went north to King and south to Albert and marched east on these streets to the point where they converge near the Church of England. Everything within the triangle having its base upon Water street and its apex at the Episcopal church was burned. This church with its detached parsonage and Sunday school escaped, although buildings on all four sides of it were consumed. The fire was not altogether stopped at the church. It burned a number of dwellings and tenements along O’Brien street northeasterly, and burned a lot of dwellings and the Presbyterian church east of the Church of England on King street. A block of dwellings, of which Dr. Haley’s was one, on the south of King street, was also consumed.

“A district of a mile in length by half a mile in width is nothing but a mass of smoking embers, with ghostly chimneys rising like ugly monuments in a huge cemetery…”

Three buildings not mentioned did survive in that area. One was the former tavern with the high stone wall across from Christ Church on King street. The second was the Baptist parsonage not quite completed adjacent to the former tavern on King street. The third was the residence of Godfrey P. Payzant, then occupied by his daughter and son-in-law, Emma and Robert Paulin, at the corner of King and Albert streets. “It is stated that R. Paulin will donate $1,000 to the Halifax firemen for saving his house.”

The collection of paintings was moved to the lawn in case they needed to be taken to safety. Before that could be done, falling embers burned through the canvases and damaged them seriously. The building is now occupied by Evangeline Trust Company, and the restored paintings are back on the walls.

“Had the buildings been of paper, saturated with oil, they could not have sprung into flame quicker than they did. In an instant almost the whole of the area between the starting point of the fire and the Windsor Foundry [near the corner of O’Brien and King] and the portions flanking each side of the line drawn in that direction, were in flames.

“The firemen attached their hose to what hydrants they could. They hardly knew what they were doing, so fearful was the onset of the fiery enemy. Driven from the hydrants by the unbearable heat, they uncoupled their hose, and in a number of instances were forced to beat so hasty a retreat that they left the water pouring full force from them into the gutters. Retreating before the fire, they attached their hoses to other hydrants…”

“… A unique spectacle was presented by a central figure in the great collection of unfortunate women and children looking after what was left of their household goods. The men were in the town watching the flames eating up the last remnants of their homes… a team laden ten feet deep with bedding and furniture completely enveloped in flame… The poor man who thought he had at least saved part of his goods was dismayed to find he was losing all he had. Others in less trouble than he tried to save a piano that formed a background of the load by removing the lighter stuff, but this could not be accomplished, for faster than they could work did the fire penetrate the inflammable material and ere the balance of the load had been removed the valuable piano was burning like the rest.”

One of the witnesses as a child, remembered through life a row of table-top rosewood grand pianos in the street. As the most valuable furniture in many homes, they had been removed first, and there they stood burning. “The remains of over one hundred pianos were counted in the ruins yesterday, and hundreds of charred bodies of dogs and other domestic animals. Nearly every house had put in a winter’s supply of coal and the sight of hundreds of burning piles of coal is an interesting spectacle.”

“When the chemical engine reached Water street, the fire had swept the town north, west and south, and was rushing with giant strides up Chapel lane. It had swept the little Roman Catholic church out of existence, had demolished the Methodist and Baptist churches, and the Presbyterian had ignited…

“The flames pent up in the residences, burst through the heavily-glazed windows with a roar like exploding cannon, and the crackling of the fire, fanned to fury by the gale made a fearsome sound never to be forgotten. The street was impassable to all but the most daring. The hurricane swept down from the northwest, carrying before it clouds of dust and small gravel, masses of burning embers, and a volume of smoke that seemed almost as painful to the eyes as would be the flames themselves…

“The scene last night at Windsor was one of desolation. A strong wind from the north blew with great velocity across the ruins, carrying embers and countless sparks a long distance. It was piercingly cold. Many of those who had lost all their belongings in the flames gathered on the college grounds and spent the night under canvas. Two large marquee tents and several bell top tents were erected by the military.

“The spot chosen was the thicket in the vicinity of the college. Many of the victims of the fire with their children were seated on the long platform leading from the street to the college, waiting for a place of shelter. Some were very poorly clad. They had lost all their effects, and escaped only with what they wore. The flames spread with such rapidity that few managed to save anything. The articles that were saved were placed in open fields and the owners kept watch over them. Some remained all night in the open air, watching their effects.

“The hundreds of mattresses sent from Halifax did good service. Those who were able to pay for board and lodging besieged the Dufferin hotel. By 8 o’clock in the evening the provisions had given out at the hotel and many were obliged to retire without supper. Host Cox was unable to meet the emergency. His hotel, the only one that escaped, was now filled with lodgers. All of the rooms were crowded and in many cases four people occupied one bed. Others were supplied with shakedowns in halls, offices, and dining rooms.

“Between 8 and 10 o’clock trains arrived from Kentville, Hantsport and other places crowded with people anxious to ascertain the whereabouts of their friends. Many of those who had lost their homes found shelter in King’s College, where they were made as comfortable as possible. A number of mattresses were placed in the railway station. A large number of the homeless soon gathered there. Drillio’s barn and sail loft in the vicinity were also packed with people. Hundreds of shakedowns were brought into service…

“… During the night the walls that were considered dangerous were razed by the Royal Engineers. Gun cotton was placed under them and the explosions that followed resounded all over the burnt district, and the remainder of the town. Hundreds of small fires burned during the night. At one time the entire ruins were a mass of flame, the sparks from which were carried for over a mile.”

At 9:30 there was a fire alarm and the firemen turned out and halted the fire from spreading. “It looked as though the remaining portion of the town might be wiped out.”

“… Military sentinels or watchers, armed with rifles, took up their positions in different parts of the ruins to give an alarm in case the strong wind caused another outbreak of flame, and… to watch over the partially burned effects left behind by their owners.”

When the trainloads of provisions arrived “they were placed under the protection of the military, who patrolled in front of the cars all night, with fixed bayonets. The mob that had gathered soon dispersed and by midnight the soldiers were the only ones on the scene. It was the worst night that Windsor had ever seen…

“The scene in the smoking and dining rooms of the Dufferin hotel was one never to be forgotten. Kind hearted proprietor Cox left those apartments open to the homeless. Many took advantage of the offer and occupied all the chairs and sofas available…”

There were about fifty people in these rooms.

Captain [Clarence Hoyt?] Dimock of the militia, in Rawdon, rode into town eighteen miles in an hour and a quarter on hearing of the crisis. “He dashed through the burning streets, but was too late to save the effects of the militia department. Every rifle was burned and all of the uniforms and equipment.”

There were many, many personal stories of bravery and sadness. Father Edmund Kennedy (later Monsignor) of the Roman Catholic Church had a valuable collection of books put together over forty years. He lost all of them. They were not insured. “When I saw the fire travelling rapidly in the direction of the Roman Catholic Church I, with others, endeavoured to save some of its contents. The flames caught the church in an instant; the building was in flames. The roof was on fire, and the latter end where the door was located was in flames and smoke. I smashed the nearest window, and at the risk of my life I made it through the smoke and fire to the Blessed Sacrament and saved it.”

He no sooner got back out the window when the supporting beams gave way. He was wearing his only clothes that survived.

Captain Dimock took charge of the militia and posted guards at the bank vaults and the vault of the registry office of the former Court House. He might have been shocked had he known one of the items in that vault was a new wedding dress. It survived to be worn at the wedding.

“The advance of the fire was ended with Walter Lawson’s house on one side of King street, and the house immediately before that of George D. Geldert, a little further along, and within a few yards of the rear of the Church School for Girls, whose pupils looked with terrified yet gladdened eyes on the termination of its flaming march.”

Edgehill School for Girls had been somewhat the crowning achievement of the geologist and explorer Henry Youle Hind, who had campaigned strenuously for its building, and succeeded in getting a cornerstone laid in 1891. The huge wooden building that was the school developed gradually on the site, and Hind used to sit in the tower room and contemplate the wonderful view across the fields and hills. The school could have gone as instantly as other institutions did.

Telegraph lines were down in all directions, and some railway ties were burned and rails twisted by the heat. A section of the line passed through the inferno along Water street to Stannus street, and again across Albert street. A work train from Kentville arrived that night and the crew worked all night to restore operation of the line.

“A large number of those burned out were taken to Rawdon, Hantsport and Kentville. Some time before the fire reached the jail the seven prisoners confined there were liberated by the jailer’s daughter.”

Again and again, reports of fatalities turned out to be untrue. People had fled where they could. One couple thought missing were in Rawdon where they had taken shelter. Kentville offered accommodation for two hundred people. There were three hundred in Falmouth. Edgehill school, like King’s, opened its premises to the sufferers.

“… the Hantsport fire brigade, under the direction of George W. Churchill, practically stopped the conflagration in a house near the corner of Chestnut and Gray streets. Had this house been consumed, nothing could have saved the large block of neighbouring houses… Charles Davidson was early on the scene, and, taking in the situation at a glance, did one of the wisest things of the day, for he headed his wheel for home and immediately loaded his team with provisions from his own store and that of S.H. Mitchener, and hastened again to Windsor with substantial relief. He was followed by Edw. Coon with another load, hastily gathered from homes of citizens and from the stores. A large number of teams also drove up and brought safety and comfort to many women and children.” by train, on the maiden voyage of the invincible White Star liner Titanic, and went down with the ship.

As much as the town appreciated the generous and immediate assistance that came from all directions, there may have been some bewilderment and even annoyance that outsiders seemed to be meddling as well.

At the meeting of the Council on 16 December a letter was read from W. Medford Christie, town solicitor, outlining some of the events that had not been recorded previously.

“On the evening of the day of the fire, His Honor Lieutenant Governor [Malachy Bowes] Daly [three years short of his KCMG and Sir], General Montgomery Moore, His Worship Mayor [Alexander] Stephen of Halifax, His Worship Mayor Marsters of Kentville, His Honor Judge [John Pryor] Chipman, and a number of other gentlemen from Halifax and neighbouring towns, who had come together in Windsor to render assistance to the distressed, together with the Mayor and a number of citizens of Windsor, met at the Hotel Dufferin and held an impromptu meeting, at which the question of the relief that was needed, and the body or persons who should have the control of the relief funds and goods together with the mode of distribution of the contributions which should come in, were discussed.

“After discussion of the question by those present, a resolution was passed appointing the Mayor and Town Council of the Town of Windsor, an executive to receive contributions, and to distribute the same to those in need of relief, with power to add to their number.

“On the following day, the Town Council met in a room in the Hotel Dufferin, and after the above facts were stated, on motion it was resolved in substance, that the Town Council be and act as a Relief Committee to receive and distribute the funds and supplies which had been and would be sent in to relieve the distressed.

“A resolution was also passed, appointing certain gentlemen of the Town on the Relief Committee, to assist in the work of distributing the relief.

“A meeting was afterwards held in the Avonian [Cycling] Club Rooms at which the foregoing facts were stated by your Worship and the names of other gentlemen were suggested as persons who should be appointed on the Relief Committee, and their names were added. The Town Council and clergymen were appointed a financial committee.

“My opinion is that the Town Council is the only body which has any legal standing in this matter. The Mayor and Council can be held responsible for the proper administration of the funds. The funds do not belong to the Town of Windsor for the general purpose of the town; but are held in trust for the purpose of relieving the distress of those who, by reason of losses by the fire, are deprived of the means of subsistence, and are suffering for the necessaries of life.

“In order to obviate any misunderstanding or friction that may exist, or which might in future arise as to the body or persons who have the control of the relief funds or the right to decide on the way the relief should be distributed, I beg to suggest, that at the next meeting of the Legislature of Nova Scotia, the Town Council apply for an act appointing and incorporating certain persons to be a board of relief under whose control the funds shall be placed and who will attend to the distributing of them.”

When the Legislature sat, this was done, and the act was passed by the House on 7 March 1898. (L.S. Loomer – A Journey in History)