On the 3-4 November 1759, the Maritimes was struck by one of many storms that marked its history. It is comparable to the storm of 1711 and the gale of 1775 gale that killed around 2000 people. Those storms were so severe that they were epoch-marking, so much so that events are dated as “before” or “after” the big storm.

The Storm of 1759 happened at the time when Acadians were still being deported – the Acadian Deportation lasted from 1755-1762. As with this hurricane, major damage was sustained in 1759 all along the coasts of Acadie and the Atlantic provinces. Fortunately, there were no reported fatalities in 1759 and destruction of homes was less since most Acadians had been deported and many of their homes destroyed by British troops. Here is how the historian Beamish Murdock describes the Storm :

“On the night of the 3-4 November, 1759, Saturday night and Sunday morning, the most violent gale of wind occurred at Halifax that had ever been known. Vast damage was done to wharves, and the salt and sugars in the stores on and near the beach were almost wholly ruined. Two schooners were driven ashore. Thousands of trees were blown down, and in some places the roads were rendered impassable. Several thousands pounds loss was computed to have been sustained … The storm broke down the dykes on the Bay of Fundy everywhere, and the marsh lands now deserted were overflown and deteriorated… The tide was supposed to have been raised 6 feet perpendicular above its ordinary level. The storm broke down the dykes on the Bay of Fundy everywhere, and the marsh lands now deserted were overflown and deteriorated. At Fort Frederick, on Saint John river, a considerable part of the fort was washed away; and at fort Cumberland, 700 cords of firewood was swept off by the tide, in a body, from the woodyard although situated at least ten feet higher than the tops of the dykes.”

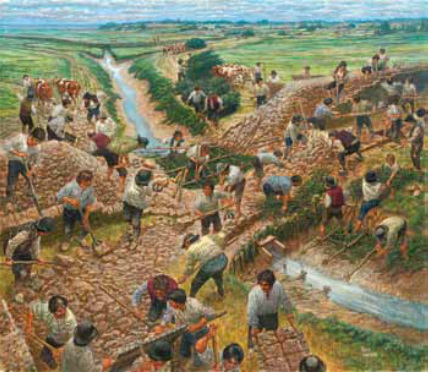

In the Minas Basin, the storm greatly damaged the aboiteaux and the levees constructed by the Acadians, some going back to the 1680’s. By the 1740’s, that region of Acadie compared advantageously with other rural areas of New England and New France. The Acadian ”pastures, grain field, and gardens produce were said to be the finest in quality, and in quantity per acre, of any farms along the Eastern Seaboard.”

The Storm struck four years after the maintenance and repairs to the dykes was abandoned due to the fact that the majority of the population of Minas Basin had been deported in 1755.

Acadian prisoners to the rescue of the British settlers

The storm greatly impeded the Planters settlers from New England in Acadie. So the Acadians prisoners at Fort Edward were called for help. The new settlers petitioned the Halifax government to intervene because they were at a lost without the expertise of aboiteaux maintenance of the prisoners.

In June 1761 Jonathan Belcher, president of the Nova Scotia Assembly, responded that ”it appeared Extremely necessary that the Inhabitants should be assisted by the Acadians in repairing the Dyke in which they are the most skillfull people in the Country.” Colonel Forster, responsible for the Acadians detainees, advised Belcher that he could have about 120 prisoners; but since they could hire themselves to worked on military installations in Halifax at a shilling a day, they declined to go to Minas Basin.

In the last part of 1761, nearly 200 Acadians prisoners were conscripted to works across Nova Scotia. It appeared that the Acadians received a higher wage, because in 1762 they were paid 2 shillings per day. In 1764, Jonathan Crane from Cornwallis, mentioned that two Acadians supervised the repairs to the levees and aboiteaux of Cornwallis. ”I have attended the making of Dikes, and Aboiteaus since the year 1764: was present when the first Aboiteau of any consequence was made here by the English – which was superintended by two Frenchmen, and observed their proceedings.

At Fort Cumberland, the prisoners were also conscripted to work on settlers’ marches and levees. But there, some settlers had refused to pay them wages. In February 1763, the Provincial Secretary Bulkeley wrote to the commander of the fort ”directing that the inhabitants by instructed to pay immediately any debts owed to Acadians for labour”.

Acadians tenants on Planters farms

In 1763, the Acadians were released from prisons, but since they were forbidden to hold lands in Nova Scotia, they became tenants to well-off farmers in the area of various forts at Annapolis, Fort Edward and Cumberland. In the spring of 1764, about 12 families left for the Halifax area. In 1765, Planters from Kings County, Minas Basin, send a petition to the governor in Halifax asking to allow the Acadians, numbering about 300, to remains there, as they were most useful as labourers, and specially in repairing the dykes destroyed by the Storm of 1759.

Between 1764-1770, little is known of the day to day lives of those 300 Acadians in the Windsor/Falmouth area. How did they perceive the Planters now occupying their houses, barns and fields? In return, how do the latter perceived these former Acadians prisoners who, in 1755, Governor Lawrence & Co. had ”undertaken to rid ourselves of one of the plagues of Egypt”! In 1764, Governor Wilmot of N.S. writing to London, mentioned that ”these people. have been the bane of the Province, and the terror of its settlements. including the many mischiefs they committed”

Yet we know that some of them laboured in repairing the dykes and aboiteaux of the Planters; that about 25 families were tenants on the estates of DesBarres, Deschamps and Faesch at Falmouth and Windsor; we know roughly about the daily chores and responsibilities of tenants/proprietors, etc. It must have been strange for those tenants, working for Planters who were living in Acadians houses; houses built by their Acadians cousins in the 1730-40; while themselves were living in huts around those farms.

A few of them, old captains of schooners and mariners before 1755, were hired for their expertise on the coasts, harbours and rivers of the Maritimes, and were deemed essential for the cartographer DesBarres in his surveys for his Atlantic Neptune. He mentioned that ”the Acadians were the best for the job, since they were familiar with both shallops and the inshore waters so much so that others mapmakers of the Maritimes, Holland, Montresor and Wright also hired those old ”loups de mer” who had been sailing these waters since the days of Old Acadie. Others were supplied with basic foods rations but ”they are obliged to work in opening Roads and communications into the principal parts of the country.” A few workers built Fort Franklin in Truro, Nova Scotia; some were given permission to operate a ferry from Parrsboro to other Minas Basin ports.

Some of those Acadians, maybe about 75 families, fathers, mothers and children in the Minas Basin area stayed there till 1768-1770. They then moved to Minoudie, Cumberland Co., Nova Scotia and the Memramcook-Petitcodiac, New Brunswick, where they became tenants on the vast estates of DesBarres. In Minoudie, they had to signed lease agreements that lasted 999 years. In Memramcook, their descendants were still beholden to the Desbarres family until the 1860’s. A great majority of those were the ancestors of the first Acadians to move to the Boston area between 1880-1920.

Author’s note: The information herein was gleaned from various history texts and research papers held at the West Hants Historical Society and elsewhere. – JDW 2017

Editor’s note: The image featured here is from www.paysagedegrand-pre.ca/les-acadiens-et-la-creacuteation-du-marais-1680–1755.html

About the author:

John D. Wilson is a lifelong resident of Nova Scotia. Born in Windsor Forks in 1939, he followed a career in the computer field. In 1975 John joined the Engineering Technology Department of the Nova Scotia Institute of Technology where he taught Electronic and Computer Technology. He led in the establishment of a number of training programs including the Automated Manufacturing Technology Program. John later joined the Adult Training Division of the Department of Education from which he retired in 1997.

John and his life partner, Laura (Baxter), live in Wentworth Creek where they raised two daughters who have given them the precious gift of three grandchildren.

History and genealogy have been John’s passion from childhood, West Hants Historical Society offered him a wealth of information on the community and its people. Here he studied records, assisted visitors from all over the world and developed deep friendship with fellow volunteers. He has served in many capacities with WHHS from volunteer, to researcher to President. John has researched a great deal of the history of Hants County and has written a number of related articles that he wishes to share on this Website.